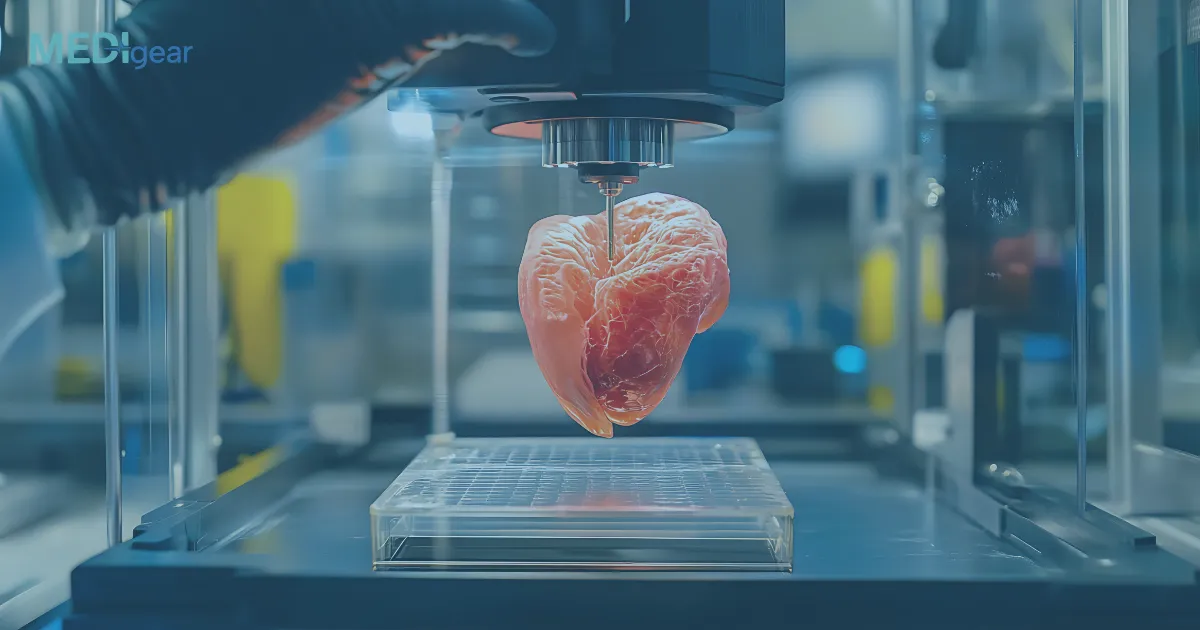

The ability to engineer living tissues and organs has long been a goal of regenerative medicine. In recent years, bioprinting technology — a specialized form of 3D printing using biological materials — has brought this vision closer to reality.

By combining cell biology, biomaterials, and computer-aided manufacturing, bioprinting systems can fabricate complex tissue structures that mimic the architecture and function of human organs. These advancements are transforming transplantation medicine, drug testing, and tissue engineering.

1. What Is Bioprinting?

Bioprinting is an advanced additive manufacturing process that uses bio-inks — mixtures of living cells, growth factors, and biomaterials — to create three-dimensional biological structures layer by layer.

Unlike conventional 3D printing, which uses plastics or metals, bioprinting focuses on replicating the microarchitecture and cellular composition of natural tissues.

The goal is to generate functional biological tissues for research, therapeutic implantation, or drug development testing — all while minimizing the need for donor organs.

2. Key Components of a Bioprinting System

A bioprinting system typically consists of:

- Bio-ink: A gel-like substance containing living cells and biomaterials such as collagen, gelatin, fibrin, or alginate.

- Printhead: The component that deposits bio-ink layer by layer according to digital blueprints.

- Bioprinter platform: Provides a controlled environment (temperature, humidity, sterility) to support cell viability.

- Software: Translates medical imaging data (like MRI or CT scans) into 3D printing instructions for precise anatomical accuracy.

Together, these elements allow bioprinters to recreate the structural complexity and mechanical properties of living tissues.

3. The Step-by-Step Process of Bioprinting

a. Pre-Processing: Designing the Blueprint

The process begins with 3D imaging — often MRI or CT scans — to capture the shape and structure of the target organ or tissue.

Computer-aided design (CAD) software then converts this data into a printable digital model.

For example, a custom cardiac patch can be modeled precisely to match a patient’s heart defect.

b. Bio-Ink Preparation

Bio-inks are formulated by mixing patient-derived cells (such as stem cells) with biocompatible materials that provide a scaffold for cell growth.

The properties of the bio-ink — including viscosity, stiffness, and nutrient content — are optimized depending on the type of tissue being printed (e.g., soft tissue vs. bone).

c. Printing the Tissue Structure

The bioprinter deposits layers of bio-ink according to the digital model.

Each layer is carefully aligned to replicate the spatial distribution of cells and extracellular matrix found in real tissues.

Techniques vary depending on the desired resolution and tissue type:

- Inkjet bioprinting: Ejects droplets of bio-ink using thermal or acoustic forces.

- Extrusion-based bioprinting: Continuously dispenses bio-ink through a nozzle — ideal for viscous materials and complex geometries.

- Laser-assisted bioprinting: Uses focused light to position cells with high precision.

d. Post-Processing and Maturation

Once printing is complete, the construct is transferred to a bioreactor, where it matures under physiological conditions.

This stage supports cell differentiation, vascularization, and tissue stabilization, allowing the structure to develop biological functionality.

Over time, the cells organize themselves into functioning tissues — for instance, forming blood vessel networks or muscle fibers.

4. Types of Tissues Being Bioprinted Today

While full organ printing is still under development, several types of functional tissues have already been successfully produced:

- Skin grafts: Used for burn treatment and wound healing.

- Cartilage and bone tissues: For orthopedic and craniofacial reconstruction.

- Cardiac patches: Repair damaged heart tissue after myocardial infarction.

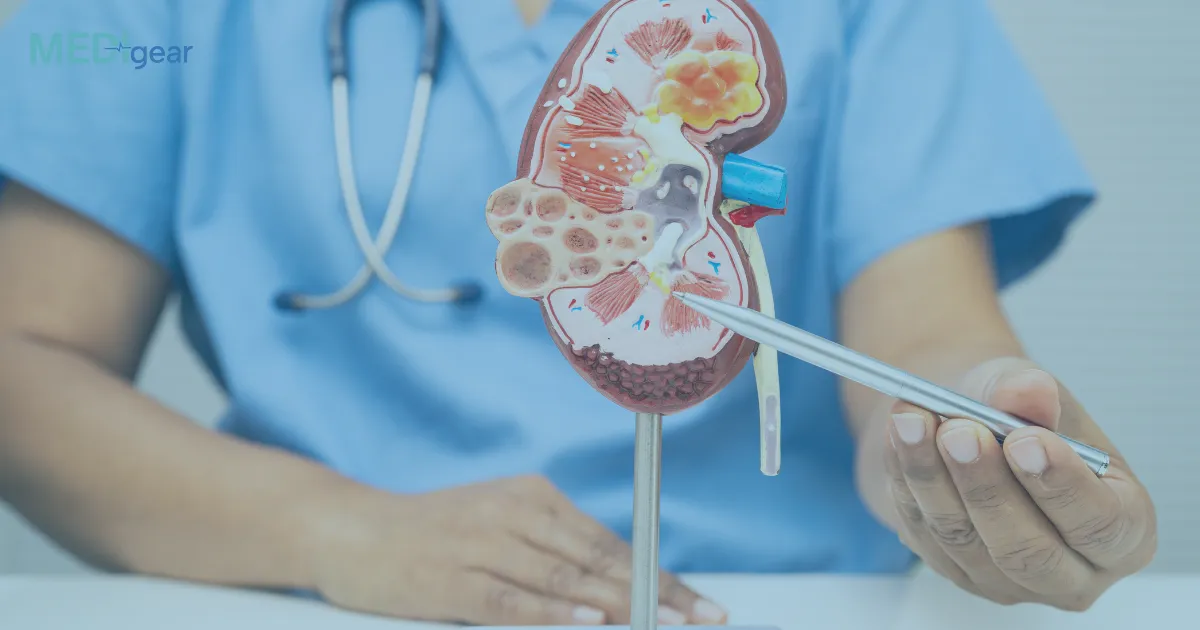

- Liver and kidney models: For drug toxicity testing and pharmaceutical research.

- Vascular structures: To support nutrient delivery in larger printed constructs.

5. Advantages of Bioprinting

a. Personalized Medicine

Bioprinting allows the creation of patient-specific tissues using their own cells, reducing the risk of immune rejection.

b. Reducing Organ Shortages

As global demand for organ transplants continues to rise, bioprinting offers a potential long-term solution by generating customizable, lab-grown organs.

c. Safer Drug Development

Pharmaceutical companies can use bioprinted human tissue models to test drug efficacy and toxicity — minimizing reliance on animal testing.

d. Accelerated Tissue Engineering Research

Bioprinting enables scientists to study disease mechanisms and regenerative processes in a realistic, 3D cellular environment.

6. Challenges and Limitations

Despite remarkable progress, bioprinting still faces scientific and ethical hurdles:

- Vascularization: Ensuring printed tissues have proper blood vessel networks for oxygen and nutrient delivery.

- Cell viability: Maintaining living cells throughout the printing and maturation process.

- Mechanical stability: Achieving the strength and elasticity of natural tissues.

- Regulatory approval: Establishing safety and efficacy standards for human implantation.

Researchers are addressing these issues through innovations like bioactive scaffolds, stem cell differentiation protocols, and AI-driven design optimization.

7. The Future of Bioprinting

The next generation of bioprinting systems aims to produce fully functional organs such as hearts, kidneys, and livers suitable for transplantation.

Advances in 4D bioprinting — where printed tissues can adapt or self-heal over time — are also on the horizon.

Collaborations between academia, biotech firms, and regulatory agencies are driving the field toward scalable, clinically applicable solutions that could redefine regenerative medicine within the next decade.

Final Thoughts

Bioprinting systems are revolutionizing the way we approach tissue engineering and transplantation.

By precisely layering living cells and biomaterials, these technologies are enabling the creation of artificial tissues and organ structures that closely mimic nature.

While full organ fabrication is still a future goal, ongoing innovations in biomaterials, stem cell science, and computational design are paving the way for a new era of personalized, regenerative healthcare.

Disclaimer:

This article is for informational purposes only and does not replace professional medical or scientific advice. For research or clinical applications, consult qualified biomedical professionals or regulatory authorities.